But times change, and now notes strike me as an alluring luxury, and I have gradually augmented my old beautifully illustrated set of Dickens with Penguins with notes. I recently bought a new Penguin of Little Dorritt , with excellent notes by Stephen Wall and Helen Small. If you’re not in a rush, it’s fun and interesting to read in Little Dorritt, for instance, that Beau Nash was “Richard Nash (1647-1762), professional gambler and leader of fashion..... he did much to establish the reputation of Bath as a society resort, and became popularly known as the ‘King of Bath.’“ (Notes to Book the First, Chapter 9, Note 9 of Little Dorritt, Penguin 2009.)

Illustration from Little Dorritt by Phiz

My copy, alas, was printed without the appendices. A note refers me to Appendix 1: there is no Appendix 1. A note refers me to Appendix 2: there is no Appendix 2. I’m sure the appendices are fascinating, too, but missing in my copy.

I once bought a novel with pages printed out of order and some missing - and the publisher kindly replaced the book. But at the Penguin website I couldn’t find quite the right person to contact. That’s the problem with corporations. I received an automatic e-mail reply that seems to have registered me in a forum.

Recently, notes have also featured in my other reading.

THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS: Two annotated versions of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows have been published this year. They have been reviewed in The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The New York Review of Books.

Illustration from The Wind in the Willows by Wyndham Payne (1927)

“Why are they both published this year?” a friend asks.

Good question.

The centenary was last year, and perhaps it is related to that. The "dueling editions" have been published by Harvard University Press and Norton.

I bought a copy of the excellent edition edited by Seth Lerer (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press). Lerer’s notes are not intrusive: they are printed on the sides of the page with the text. And they are not stuffy: they often refer to the OED, in which he traces slang like “spring cleaning,” which first appeared in the OED in 1857, and reflected changing 19th-century domestic habits, with their emphasis on cleanliness and sanitation. He defines “scrooged,” a variation of “scrouge,” meaning to crowd or push. Who knew? He cites references to Milton, Wordsworth, and Shakespeare, which Grahame definitely knew, having edited The Cambridge Book of Poetry for Children in 1899. He even includes a photo from a furniture catalogue to complement the description of Badger's home.

The introduction is fascinating, analyzing The Wind in the Willows as belonging to the tradition of humorous travel novels like Three Men in a Boat, animal fable, theater, etc.

One of the most appealing aspects of the book is the illustrations. I grew up with a copy with the E. H. Shepard illustrations. The text of Lerer's Annotated edition is illustrated with Shepard's, but there are also beautiful colored plates in the middle of illustrations by Paul Bransom (1913), Nancy Barnhart (1922), Wyndham Payne ( 1927), my favorite, Philip Mendoza (1983), and more.

The Wind in the Willows is charming: as a talking animal book, I rate it beneath Watership Down but above Winnie the Pooh. For an adult, the experience of reading is improved by the notes. Otherwise, I must admit, I’d be tempted to read a chapter and then put it away. It is very difficult to reread children’s fantasies, which often are spoiled by being filtered through our adult sensibilities.

THE SECRET GARDEN: After reading Julie Buxbaum's After You, a novel with allusions to The Secret Garden, I had to buy The Annotated Secret Garden (Norton), edited by Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina, Frances Hodgson Burnett’s biographer. Buxbaum mentioned in her acknowledgments how inspiring she had found Gerzina’s biography and The Annotated Secret Garden.

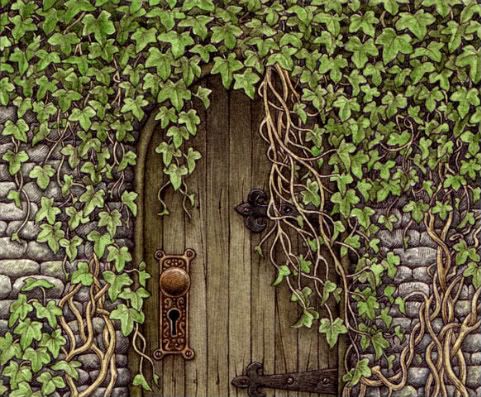

Illustration from The Secret Garden (Folio Edition) by Robert Barnett

So I had to have it! I haven’t read it yet, but the illustrations are fascinating. I grew up on Tasha Tudor’s, but she provides us with earlier illustrations that are equally charming. (By the way, I want the old SECRET GARDEN DIARY: The Perfect Gift for Anyone Who Loves Keeping Secrets, which is pictured in the introduction. I would also like the bracelet made from illustrations from The Secret Garden!)

2 comments:

Sometimes the notes are the most fun part of a book, especially when it is one of these illustrated newly-got up editions of well-known texts. But it can be just any book where the author is ironic in his or her notes in ways they can't or aren't in the body of the text.

I've been complimented on my notes a number of times -- as if what's there is better than the text :)

Ellen

The notes are a separate world: they constitute their own text.

There is a recent first novel - the title might have "Spivey" in it, but I can't remember - with the character's fictional notes and illustrations on the side of the page.

I've always admired your notes.

Post a Comment