After six years at Frisbee: A Book Journal, I am moving to a new site.

Please visit my new blog, mirabile dictu, where I will continue to publish my reviews, essays, and musings about the 21st-century life-style.

The url is http://mirabiledictu.org

See you there!

Frisbee: A Book Journal

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Tuesday, December 18, 2012

Seven Days Till Christmas or the Materialistic Nightmare

There are seven days till the Materialistic Nightmare. I haven't bought a last-minute fixie bike, "Lazy Housekeepers Mop Slippers," or an iPhone.

My husband said he would spend the day in the garage if I got him an iPhone.

One book per person. That's what we're giving for gifts. Last year I was pushing a cart at Target in a daze, filling it with random items that nobody much wanted.

It was the worst Christmas ever.

So this year we are having a less materialistic Christmas. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir on the old stereo, the fiberoptic Christmas tree, and the afternoon viewing of Love Actually or Bullitt (we haven't decided yet).

I may not be able to compile a gift list as varied as that of Kelly and Michael Live!, but I do know how to shop for books. My list is divided into four categories: Books You Can Give Anyone, Contemporary Classics, Women's Novels (N.B., for anyone really, but I know from experience that my husband won't read these), and Nonfiction.

Category One: BOOKS YOU CAN GIVE ANYONE, OR ONE SIZE FITS MOST.

1. Anything by P. G. Wodehouse. Need a last-minute Christmas gift for a forgotten friend? Put a Wodehouse comedy in the Christmas stocking or the mail. The Bertie Wooster and Jeeves series (about foppish Bertie and Jeeves, the percipient, problem-solving valet) and the Blandings Castle books (about absent-minded Lord Emsworth and his prize-winning pig, the Empress) are the most popular, but he wrote nearly 100, and most are good. These classics are available in beautiful Overlook Press hardcovers or Norton paperbacks. And the early books are available free as e-books at manybooks.net

2. Are you short of money? You can always send a link in an email to a list of free e-books at manybooks.net

My manybooks.net Christmas book list includes:

Louisa May Alcott’s "The Abbott’s Ghost"

Booth Tarkington’s Beasley’s Christmas Party

Kate Douglas Wiggin’s The Bird’s Christmas Carol

William Makepeace Thackeray’s The Christmas Books of Mr. M. A. Titmarsh

and more you've never heard of.

Category Two: CONTEMPORARY CLASSICS

1. Will Self's Umbrella, a Man Booker Prize finalist. This dazzling labyrinthine Joycean classic deserves a closer reading than I was able to give it last fall, so I have a date to reread it in January. There should be an Umbrella chat somewhere. Is there one?

Here is the book description on the cover.

"Radical and uncompromising, Umbrella is a tour de force from one of England’s most acclaimed contemporary writers, and Self’s most ambitious novel to date. Moving between Edwardian London and a suburban mental hospital in 1971, Umbrella exposes the twentieth century’s technological searchlight as refracted through the dark glass of a long term mental institution. While making his first tours of the hospital at which he has just begun working, maverick psychiatrist Zachary Busner notices that many of the patients exhibit a strange physical tic: rapid, precise movements that they repeat over and over. One of these patients is Audrey Dearth, an elderly woman born in the slums of West London in 1890. Audrey’s memories of a bygone Edwardian London, her lovers, involvement with early feminist and socialist movements, and, in particular, her time working in an umbrella shop, alternate with Busner’s attempts to treat her condition and bring light to her clouded world. Busner’s investigations into Audrey’s illness lead to discoveries about her family that are shocking and tragic."

2. A Lovesong for India: Tales from East and West by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. This exquisite collection of short stories by Jhabvala, who won the Booker Prize for her novel Heat and Dust and two Academy Awards for best adapted screenplay for Merchant-Ivory films, A Room with a View and Howards End, is one of the best books I have read this year. Some stories are set in India, where Jhabvala lived for many years, and others in the U.S., where she lives now, and the collection is divided into three parts, “India,” “Mostly Arts and Entertainment,” and “The Last Decades.”

3. The Watch by Joy Roy-Bhattacharya. This luminous retelling of Antigone, set during the ongoing war in Afghanistan, is about soldiers and civilians, brothers and sisters. One of the best books I read this year, and I cannot imagine why it is not on everybody's "best of" books.

Category Three: Women's Novels (Novels by and about Women)

1. In the Kingdom of Men by Kim Barnes. Carson McCullers’ Frankie in Member of the Wedding meets Ginny Babcock in Lisa Alther’s Kinflicks meets Real Housewives of Saudi Arabia. The narrator, Gin, a fundamentalist minister’s granddaughter raised in poverty in Oklahoma, is one of those likable, smart, passionate characters we like to spend time with. But if you thought you’d like to grow up and be the wife of an oil man in Saudi Arabia in 1967, think again. Fascinating and well-researched.

2. The Red Chamber by Pauline A. Chen, an unputdownable retelling of the famous 18th-century Chinese classic, Dream of the Red Chamber. I loved this story of three Chinese women of the 18th century who must angle for power, love, and money from the depths of the Women’s Quarters, where their lives are largely determined by choices of parents and husbands (and an evil grandmother), and the vicissitudes of imperial politics.

3. Sherry Jones's Four Sisters, All Queens, a lively historical novel about four sister queens in the 13th century, Queen Marguerite of France, Queen Eleonore of England, Queen Sanchia of Germany, and Queen Beatrice of Sicily. Fascinating, entertaining, and unputdownable for those of us who love historical novels. Jones is an excellent writer.

4. The Chaperone by Laura Moriarty. A charming, enjoyable novel about Cora Carlisle, a 36-year-old Wichita housewife who chaperoned Louise Brooks one summer in New York. Louise, raised in Wichita, has, at age 15, won a place at a prestigious dance school, Denishawn School of Dancing in New York. Cora, the respectable wife of an eminent lawyer, has an ulterior motive for wanting to go to New York, but learns a lot from Louise.

5. I love Bloomsbury Reader, an e-book series of reprints of women's books, mysteries, etc. This year I discovered Angela Huth, and loved her Invitation to the Married Life, which I somehow never got around to blogging about, about four married couples whose lives change unexpectedly at a party.

6. Jo-Ann Mapson's Solomon's Oak and the sequel, Finding Casey. I read and loved Solomon's Oak, in which three characters deal with grief: Glory, a 38-year-old widow, struggles to support the farm after her beloved husband’s death; Joseph Vigil, an ex-cop, was wounded in a drug bust and is looking for peace in photography; and Juniper, a 14-year-old girl, lost her sister, Casey, who was abducted, and then her parents: one abandons her, the other commits suicide.

I haven't read Finding Casey yet, but it's always nice to give a "set" of books.

Category Four: Nonfiction.

1. Jonathan Lethem's The Ecstasy of Influence: Nonfictions, etc., a splendid collection of brilliant autobiographical vignettes, essays, reviews, and criticism. There’s a rich texture, a reined-in meandering, and a strangely casual feel to the obviously careful architecture of his nonfiction–characterized by intellectualism, self-consciousness, self-mockery, humor, and self-apology. .

2. Alice Kessler-Harris's biography, A Difficult Woman: The Challenging Lives and Times of Lillian Hellman. Hellman is a great American writer, whose books should surely be in the Library of America or Everyman Classics, but has been kicked out of the canon because she told lies. Kessler-Harris sympathetically explores the life of this free-thinking leftist.

3. Nick Hornby’s More Baths Less Talking, the fourth collection of his hilarious book columns from The Believer. At the beginning of each month he lists the "books bought" in one column, and the "books read" in another--and they rarely coincide. He always has intelligent things to say about books, but he also is very witty

My husband said he would spend the day in the garage if I got him an iPhone.

One book per person. That's what we're giving for gifts. Last year I was pushing a cart at Target in a daze, filling it with random items that nobody much wanted.

It was the worst Christmas ever.

So this year we are having a less materialistic Christmas. The Mormon Tabernacle Choir on the old stereo, the fiberoptic Christmas tree, and the afternoon viewing of Love Actually or Bullitt (we haven't decided yet).

I may not be able to compile a gift list as varied as that of Kelly and Michael Live!, but I do know how to shop for books. My list is divided into four categories: Books You Can Give Anyone, Contemporary Classics, Women's Novels (N.B., for anyone really, but I know from experience that my husband won't read these), and Nonfiction.

Category One: BOOKS YOU CAN GIVE ANYONE, OR ONE SIZE FITS MOST.

1. Anything by P. G. Wodehouse. Need a last-minute Christmas gift for a forgotten friend? Put a Wodehouse comedy in the Christmas stocking or the mail. The Bertie Wooster and Jeeves series (about foppish Bertie and Jeeves, the percipient, problem-solving valet) and the Blandings Castle books (about absent-minded Lord Emsworth and his prize-winning pig, the Empress) are the most popular, but he wrote nearly 100, and most are good. These classics are available in beautiful Overlook Press hardcovers or Norton paperbacks. And the early books are available free as e-books at manybooks.net

2. Are you short of money? You can always send a link in an email to a list of free e-books at manybooks.net

My manybooks.net Christmas book list includes:

Louisa May Alcott’s "The Abbott’s Ghost"

Booth Tarkington’s Beasley’s Christmas Party

Kate Douglas Wiggin’s The Bird’s Christmas Carol

William Makepeace Thackeray’s The Christmas Books of Mr. M. A. Titmarsh

and more you've never heard of.

Category Two: CONTEMPORARY CLASSICS

1. Will Self's Umbrella, a Man Booker Prize finalist. This dazzling labyrinthine Joycean classic deserves a closer reading than I was able to give it last fall, so I have a date to reread it in January. There should be an Umbrella chat somewhere. Is there one?

Here is the book description on the cover.

"Radical and uncompromising, Umbrella is a tour de force from one of England’s most acclaimed contemporary writers, and Self’s most ambitious novel to date. Moving between Edwardian London and a suburban mental hospital in 1971, Umbrella exposes the twentieth century’s technological searchlight as refracted through the dark glass of a long term mental institution. While making his first tours of the hospital at which he has just begun working, maverick psychiatrist Zachary Busner notices that many of the patients exhibit a strange physical tic: rapid, precise movements that they repeat over and over. One of these patients is Audrey Dearth, an elderly woman born in the slums of West London in 1890. Audrey’s memories of a bygone Edwardian London, her lovers, involvement with early feminist and socialist movements, and, in particular, her time working in an umbrella shop, alternate with Busner’s attempts to treat her condition and bring light to her clouded world. Busner’s investigations into Audrey’s illness lead to discoveries about her family that are shocking and tragic."

2. A Lovesong for India: Tales from East and West by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala. This exquisite collection of short stories by Jhabvala, who won the Booker Prize for her novel Heat and Dust and two Academy Awards for best adapted screenplay for Merchant-Ivory films, A Room with a View and Howards End, is one of the best books I have read this year. Some stories are set in India, where Jhabvala lived for many years, and others in the U.S., where she lives now, and the collection is divided into three parts, “India,” “Mostly Arts and Entertainment,” and “The Last Decades.”

3. The Watch by Joy Roy-Bhattacharya. This luminous retelling of Antigone, set during the ongoing war in Afghanistan, is about soldiers and civilians, brothers and sisters. One of the best books I read this year, and I cannot imagine why it is not on everybody's "best of" books.

Category Three: Women's Novels (Novels by and about Women)

1. In the Kingdom of Men by Kim Barnes. Carson McCullers’ Frankie in Member of the Wedding meets Ginny Babcock in Lisa Alther’s Kinflicks meets Real Housewives of Saudi Arabia. The narrator, Gin, a fundamentalist minister’s granddaughter raised in poverty in Oklahoma, is one of those likable, smart, passionate characters we like to spend time with. But if you thought you’d like to grow up and be the wife of an oil man in Saudi Arabia in 1967, think again. Fascinating and well-researched.

2. The Red Chamber by Pauline A. Chen, an unputdownable retelling of the famous 18th-century Chinese classic, Dream of the Red Chamber. I loved this story of three Chinese women of the 18th century who must angle for power, love, and money from the depths of the Women’s Quarters, where their lives are largely determined by choices of parents and husbands (and an evil grandmother), and the vicissitudes of imperial politics.

3. Sherry Jones's Four Sisters, All Queens, a lively historical novel about four sister queens in the 13th century, Queen Marguerite of France, Queen Eleonore of England, Queen Sanchia of Germany, and Queen Beatrice of Sicily. Fascinating, entertaining, and unputdownable for those of us who love historical novels. Jones is an excellent writer.

4. The Chaperone by Laura Moriarty. A charming, enjoyable novel about Cora Carlisle, a 36-year-old Wichita housewife who chaperoned Louise Brooks one summer in New York. Louise, raised in Wichita, has, at age 15, won a place at a prestigious dance school, Denishawn School of Dancing in New York. Cora, the respectable wife of an eminent lawyer, has an ulterior motive for wanting to go to New York, but learns a lot from Louise.

5. I love Bloomsbury Reader, an e-book series of reprints of women's books, mysteries, etc. This year I discovered Angela Huth, and loved her Invitation to the Married Life, which I somehow never got around to blogging about, about four married couples whose lives change unexpectedly at a party.

6. Jo-Ann Mapson's Solomon's Oak and the sequel, Finding Casey. I read and loved Solomon's Oak, in which three characters deal with grief: Glory, a 38-year-old widow, struggles to support the farm after her beloved husband’s death; Joseph Vigil, an ex-cop, was wounded in a drug bust and is looking for peace in photography; and Juniper, a 14-year-old girl, lost her sister, Casey, who was abducted, and then her parents: one abandons her, the other commits suicide.

I haven't read Finding Casey yet, but it's always nice to give a "set" of books.

Category Four: Nonfiction.

1. Jonathan Lethem's The Ecstasy of Influence: Nonfictions, etc., a splendid collection of brilliant autobiographical vignettes, essays, reviews, and criticism. There’s a rich texture, a reined-in meandering, and a strangely casual feel to the obviously careful architecture of his nonfiction–characterized by intellectualism, self-consciousness, self-mockery, humor, and self-apology. .

2. Alice Kessler-Harris's biography, A Difficult Woman: The Challenging Lives and Times of Lillian Hellman. Hellman is a great American writer, whose books should surely be in the Library of America or Everyman Classics, but has been kicked out of the canon because she told lies. Kessler-Harris sympathetically explores the life of this free-thinking leftist.

3. Nick Hornby’s More Baths Less Talking, the fourth collection of his hilarious book columns from The Believer. At the beginning of each month he lists the "books bought" in one column, and the "books read" in another--and they rarely coincide. He always has intelligent things to say about books, but he also is very witty

Saturday, December 15, 2012

The Blog Belongs to Yesterday

"The blog belongs to yesterday, I wanted to tell him."-- Zoo Time by Howard Jacobson

After a dizzying spell of scribbling rough journal entries at my blog for six years, I have begun to wonder what I am doing.

Other bloggers are also wondering, not what I am doing, but what they are doing, or perhaps not what they are doing, but why the comments at their blogs are dwindling. Since the early autumn, there has been a whine-fest in the blogosphere about the decline of comments on blogs.

Those with moxie claim their traffic is up, though comments are down. And if you believe that, you’re a journalist.

I say that to tease the journalists, who have blamed social media for ruining literary criticism. And I also like to tease my fellow bloggers, who perhaps take these numbers too seriously.

Nothing on the internet lasts. There is always the next new thing. Blogs, according to a rather vague article in Wikipedia, started in the late ‘90s. But “social media” have been around for longer. A friend told me that in the ‘80s he was busy with an online community (sorry, I don’t know the name of it). At AOL in the ‘90s, books were discussed on “bulletin boards” until the AOL site Book Central shut down. Then the book communities dwindled. And of course there are discussion groups at Google, Yahoo, etc., but the number of posts there is dwindling, too.

People have moved on to whatever they move on to: Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, Tumblir, etc.

For whom are we blogging? Numbers, or readers? The access to statistics on readership at our blogs is a surveillance feature. It reveals that my most popular post ever was about the actress Elizabeth Taylor...and why do I need to know that? Am I a corporation frantically trying to sell the most popular post? Or am I writing about books?

Blogging has changed my style of reading. I have five or six books going at a time now, instead of one or two, as though I am a book editor deciding what to read, or can’t bear the boredom of reading one. I want to be bored again.

In the ‘90s, when I posted on book boards instead of at mesite.com (or whatever you might call my blog), I talked with intelligent people about classics and excellent literary fiction. Since I began blogging in 2006, my reading has taken a downward trend. I still read classics and literary fiction, but why would I ever bother with Celia by E. H. Young (a middlebrow novel by an extremely unimportant writer) or Maidenhead by Faith Berger (basically a porn book selection at the innovative online book club Emily Books)? Yes, I learned about these books online.

Blogs are fun, but we click from one to another to another and learn about more books than we can ever read. I need to slow down.

So I don’t know what the future is. The other day I was reading dovegreyreader scribbles and Kevin from Canada, and I wondered, hm, will they still be doing this in a couple of years?

As for myself, I plan to keep blogging but to write shorter posts. I plan to be bored.

We’ll see how it works out.

Thursday, December 06, 2012

REM's Christmas Griping, Merry Capitalism, and Books to Read on the Holidays

Christmas is about Merry Capitalism. It has always been about gifts at my house.

This year we're not doing that. Everybody gets one book. That's all.

Some say they'll give gifts anyway. I don't want gifts. I don't want something electronic that fits in my purse. I don't want a goat bought for a family in Africa in my name. Let's give to charities anonymously, and if it be goats, so be it.

The rule? Don't give anything electronic or with an electric cord.

While others are opening gifts, I will turn up the heat (70 degrees is perfect), take a long bath, do some stretches to an ancient Jane Fonda tape, watch one Christmas movie (I am voting for Love Actually, but somebody else wants Steve McQueen, hardly connected to Christmas, I might add, and I think we'll be watching Bullitt!) and read books of course.

Here are five books I'll give this Christmas:

FOR FANS OF LITERARY CRITICISM BY A WRITER WHO CAN WRITE.

Nick Hornby’s More Baths Less Talking, the fourth collection of his hilarious book columns from The Believer, is one of the best books of the year. At the beginning of each month he lists the "books bought" in one column, and the "books read" in another--and they rarely coincide. He always has intelligent things to say about book, but he also is very witty about it. During a 100-mile car ride, I read parts aloud to my husband. He appreciated it, even though I'm not an audiobook.

FOR FANS OF ROCK AND ROLL FICTION:

Clyde Edgerton's charming, humorous novel, The Night Train, inspired by James Brown, Civil Rights, and friendship, is a small, deceptively simple novel. If you missed it , and you missed it if you blinked, you should check out this Southern rock-and-roll classic.Set in 1963 in the small town of Starke, North Carolina, it is the story of a music-based interracial friendship between two boys who work in a furniture-refinishing shop.

One of my favorite books of the year!

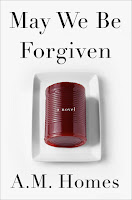

FOR FANS OF AMERICAN SUBURBAN HORROR.

A. M. Homes's new novel, May We Be Forgiven, is a horrific satire of the American Dream, laced with grief and a weird, unexpected sweetness after a tragedy undoes a wealthy family. The narrator, Harold Silver, is a Nixonologist whose brother George kills a family in a car accident, and then kills his wife after catching her in bed with Harold

The novel begins on Thanksgiving, and if you like to read about dysfunction on the holidays, you will enjoy this, but I'll warn you--it goes pretty far. Maybe too far.

FOR FANS OF GREAT WOMEN'S FICTION.

Olivia Manning's The Doves of Venus is a gorgeously-written, exuberant novel about what it meant to be female in the mid-twentieth century. This coming-of-age novel traces the career of Ellie, a young woman who leaves her home in Eastsea for London, where she finds a job painting and "antiquing" Regency furniture. She doesn't mind living in a tiny room, and is utterly intoxicated by her unfaithful lover, Quintin, the middle-aged man who seduced her and got her the promotion to work in the studio.

FOR FANS OF BRILLIANT NATIVE AMERICAN SHORT STORIES.

In the Native American writer Sherman Alexie's transcendent new book, Blasphemy: New and Collected Stories, he writes about lost cats, marriage, racism, growing up on the Spokane reservation, growing up Native American in the city without the Spokane traditions, shopping at the 7-11, cancer, alcoholism, absent fathers, obituaries, and playing basketball at midnight. His lyricism illuminates difficult moments in the difficult lives of his Native American characters, but he also deftly balances their sorrow with humor.

MORE BOOKS FOR THE HOLIDAYS TO COME!

Wednesday, December 05, 2012

A. M. Homes's May We Be Forgiven

A. M. Homes's new novel, May We Be Forgiven, is a horrific satire of the American Dream, laced with grief and a weird, unexpected sweetness after a tragedy undoes a wealthy family. Although the style is unobtrusive, this superb book is so expertly plotted that only the narrator's musings on the American Dream could keep it off the best-seller list.

The novel begins on Thanksgiving, and if you like to read about dysfunction on the holidays, you will enjoy this, but I'll warn you--it goes pretty far. Maybe too far.

The quiet narrator, Harold Silver, is a respected Nixonologist who is writing a book on Nixon and teaching a Nixon class at a college. His insanely successful brother, George, however, has achieved a titanic version of American dream: George, the raging, power-mad head of a TV news network, has a perfect wife, two children at expensive schools, a beautiful house in the suburbs, and a superabundance of money.

On Thanksgiving, George's wife Jane kisses Harold in the kitchen, and this is a bit of the American Dream for bland Harold, because nothing much ever happens to him. His life with his quiet Chinese-American lawyer wife, Claire, is based on routine and Chinese takeout.

The American Dream can only be achieved by the wealthy, and then they fuck it up. George fucks it up bigtime. He has a car accident and kills a family. Only the child survives.

Almost any paragraph in Homes's book can be picked out to convey the fascination of her unembellished prose. Here is an excerpt of gruesome dialogue at a suburban police station between police officers and Harold after George's accident.

But the situation gets worse. So much worse. And that is why the novel is at times grimly comical. Homes piles it on.

Harold stays with Jane after George is admitted to the psych hospital. They sleep together. Then George walks out of the hospital in a nightmarish daze, comes home and finds Jane and Harold in bed, and kills Jane.

From this point, the lives of both brothers fall apart. George is slapped into a fancy rich person's mental hospital, and later into an experimental survival camp for convicts.

Harold is a passive guy. He is deeply traumatized by recent events. He moves into George's house (and his wife divorces him), is cluelessly responsible for the well-being of his 12-year-old nephew, Nate, and 11-year-old niece, Ashley, both at boarding schools, and has to take care of the house, pets, and yard. Then he has a small stroke, and it is all he can do to take care of the house and its various minders. He also has reluctant sex with women he meets on the internet and at the A&P. He doesn't want relationships, but women come after him. Especially disturbed women.

He is also deeply immersed in "Nixon Studies." He meditates on the relationship between American entitlement and the American downfall, and analyzes the "psychological progression of presidents" from Kennedy to Johnson to Nixon. Harold knows Nixon was deeply flawed, and that Watergate was a crime, but he admires Nixon's tenacity, especially in China. And Harold is so out of touch with the culture that he doesn't realize his job is on the line: nobody knows who Nixon is anymore.

His relationship with the children is funny and realistic. It involves a lot of spending money on vacations to win trust, but they also become fond of one another. Nate and Ashley are both well-drawn characters. If you've attended or taught at boarding schools, you know all too well the superficially sophisticated, spoiled kids who may be as vacuous as the characters in Gossip Girl or as brave as Sara Crewe in A Little Princess or as rebellious but deeply ethical as Dan once he turns around at Plumfield in Little Men.

The kids have problems. Nate, a jock, has an illicit business lending money at school, but has also built a school in South Africa and the town is named after him. Ashley, a nice, innocent girl was seduced by the Head of the Lower School after her mother's death. She can't face all that has happened, so comes home and works on a project about soap operas, narratives, and puppet theater. Nate and Ashley insist that Harold should adopt Ricardo, the child of the couple killed in a car crash, and they take him with them to Williamsburg, VA, for a vacation.

In May We Be Forgiven, real relationships are familial, but they also revolve around spending money. One wonders what happens to the poor waifs who can't lie around the house and eat Chinese food all day. Harold even takes the children to South Africa for Nate's Bar Mitzvah. Now that is over the top.

But money is necessary to the action here. Without money, this family couldn't unravel and ravel. After losing his job, Harold would have been too busy working at something else to nurture George's American dream. (Harold does get to work on some lost short stories by Nixon, though.)

Harold, who now has relationships to worry about, muses about the sad state of relationships in American society.

Yes, this sounds like all of us.

I loved the book. I would say Homes has matured since, many years ago, I read one of her stories in which a couple sees a news story about crack and decide to try it because it looks like fun.

Now I will have to go back and see what else she has written.

The novel begins on Thanksgiving, and if you like to read about dysfunction on the holidays, you will enjoy this, but I'll warn you--it goes pretty far. Maybe too far.

The quiet narrator, Harold Silver, is a respected Nixonologist who is writing a book on Nixon and teaching a Nixon class at a college. His insanely successful brother, George, however, has achieved a titanic version of American dream: George, the raging, power-mad head of a TV news network, has a perfect wife, two children at expensive schools, a beautiful house in the suburbs, and a superabundance of money.

|

| A. M. Homes |

The American Dream can only be achieved by the wealthy, and then they fuck it up. George fucks it up bigtime. He has a car accident and kills a family. Only the child survives.

Almost any paragraph in Homes's book can be picked out to convey the fascination of her unembellished prose. Here is an excerpt of gruesome dialogue at a suburban police station between police officers and Harold after George's accident.

"Car accident, bad one. Doesn't appear he was under the influence, passed a breath test and consented to urine, but really he should see a doctor."

"Was it his fault?"

"He ran a red light, plowed into a minivan, husband was killed on impact, the wife was alive at the scene--in the back, next to the surviving boy. Rescue crew used the Jaws of Life to free the wife, upon release she expired.""Her legs fell out of the car," someone calls out of a back office.

But the situation gets worse. So much worse. And that is why the novel is at times grimly comical. Homes piles it on.

Harold stays with Jane after George is admitted to the psych hospital. They sleep together. Then George walks out of the hospital in a nightmarish daze, comes home and finds Jane and Harold in bed, and kills Jane.

From this point, the lives of both brothers fall apart. George is slapped into a fancy rich person's mental hospital, and later into an experimental survival camp for convicts.

Harold is a passive guy. He is deeply traumatized by recent events. He moves into George's house (and his wife divorces him), is cluelessly responsible for the well-being of his 12-year-old nephew, Nate, and 11-year-old niece, Ashley, both at boarding schools, and has to take care of the house, pets, and yard. Then he has a small stroke, and it is all he can do to take care of the house and its various minders. He also has reluctant sex with women he meets on the internet and at the A&P. He doesn't want relationships, but women come after him. Especially disturbed women.

He is also deeply immersed in "Nixon Studies." He meditates on the relationship between American entitlement and the American downfall, and analyzes the "psychological progression of presidents" from Kennedy to Johnson to Nixon. Harold knows Nixon was deeply flawed, and that Watergate was a crime, but he admires Nixon's tenacity, especially in China. And Harold is so out of touch with the culture that he doesn't realize his job is on the line: nobody knows who Nixon is anymore.

His relationship with the children is funny and realistic. It involves a lot of spending money on vacations to win trust, but they also become fond of one another. Nate and Ashley are both well-drawn characters. If you've attended or taught at boarding schools, you know all too well the superficially sophisticated, spoiled kids who may be as vacuous as the characters in Gossip Girl or as brave as Sara Crewe in A Little Princess or as rebellious but deeply ethical as Dan once he turns around at Plumfield in Little Men.

The kids have problems. Nate, a jock, has an illicit business lending money at school, but has also built a school in South Africa and the town is named after him. Ashley, a nice, innocent girl was seduced by the Head of the Lower School after her mother's death. She can't face all that has happened, so comes home and works on a project about soap operas, narratives, and puppet theater. Nate and Ashley insist that Harold should adopt Ricardo, the child of the couple killed in a car crash, and they take him with them to Williamsburg, VA, for a vacation.

In May We Be Forgiven, real relationships are familial, but they also revolve around spending money. One wonders what happens to the poor waifs who can't lie around the house and eat Chinese food all day. Harold even takes the children to South Africa for Nate's Bar Mitzvah. Now that is over the top.

But money is necessary to the action here. Without money, this family couldn't unravel and ravel. After losing his job, Harold would have been too busy working at something else to nurture George's American dream. (Harold does get to work on some lost short stories by Nixon, though.)

Harold, who now has relationships to worry about, muses about the sad state of relationships in American society.

"We talk online, we 'friend' each other when we don't know who we are really talking to--we fuck strangers. We mistake almost anything for a real relationship, a community of sorts, and yet, when we are with our families, in our communities, we are clueless, we short-circuit and immediately dive back into the digitized version--it is easier, because we can be both our truer selves and our fantasy selves all at once, with each carrying equal weight."

Yes, this sounds like all of us.

I loved the book. I would say Homes has matured since, many years ago, I read one of her stories in which a couple sees a news story about crack and decide to try it because it looks like fun.

Now I will have to go back and see what else she has written.

Tuesday, December 04, 2012

Ellen Moody on Women in Cyberspace & Ron Charles on PW's Person of the Year

She analyzes women's discourse by describing the ramifications of a quarrel on a women's listserv. One distressed woman said during the altercation that she would leave the list or become silent. That response, or kind of response, is very common on the net.

Ellen quotes a post by Katha Pollitt, a poet and columnist for The Nation, saying that women's lists all have this dynamic:

... sugary mutual admiration, with occasional outbursts of snark that cause conniptions. Yerra makes a personal remark, Joyce slaps her down by appealing to ‘the spirit of the list,” Yerra takes her marbles and goes home. On a coed list, or a mostly male list, a slightly snarky remark would have just been one of those things that happen. A reprimand would be be read as impossibly stuffy, and a threat to leave would be a joke. ...

Ellen points out that women's fights are not childish. She says women are culturally not supposed to argue, and that they are punished when they complain. "The punishment will be meted out; it will be presented as reasonable behavior."

She cites Carol Gilligan’s In a Different Voice, and Lyn Mikel Brown, Meeting at the Crossroads: Women’s Psychology and Girls’ Development, studies that indicate that girls are coerced into being quiet and refraining from expressing controversial opinions at age 12 because they are expected as women to be diplomatic and polite.

(I will add parenthetically that a friend who participated in one of Brown's studies as a girl assured me that she and her friends made up the answers on the questionaires.)

Ellen's article is fascinating. I agree that women are punished for complaining.

So is it a gender thing? Well...

Yes, partly.

The quote from Pollitt's comments, at least out of context, strikes me as another version of the latest received journalistic wisdom that people are too "nice" online. Niceness is ruining the brittle edgy honesty of the internet.

The web "has become friendly, well mannered, oversweet," says Nathan Heller at New York magazine, who says he misses the hostility. And social media have ruined or weakened literary critcism, according to writers at Slate, The New York Times, and The Guardian. Some say bloggers and tweeters are too "nice," others that opinions on the internet are not equal to journalists'.

In forums, you can pick your battles. If a listserv upsets you, you can leave. Why not?

AND NOW FOR SOMETHING LIGHT: Ron Charles's response to Publishers Weekly's Person of the Year, E. L. James.

Monday, December 03, 2012

The Male Book Count, or You Don't Understand Me

Astonishingly, I've read a few more books by men than I anticipated. So far I've read 45 books by men. That's 31 percent! the highest it's ever been.

|

| Book Stat Count More or Less |

I have recently read some short good books by Nick Hornby, the novelist and film writer, and Terry Pratchett, the award-winning author of the Discworld fantasies.

I even finished Le Fanu's Guy Deverell, an enjoyable Gothic novel.

Earlier I read novels by male writers who became FOBs (Friends of the Blog) when they left comments here. (I also have female writer FOBs-- a slightly higher percentage.)

I also read some books by the male dead: Dickens and H. G. Wells.

But here's the thing. Do I understand men's literature?

I think I do.

But I probably don't.

I recently talked to a male friend about Doris Lessing. And he didn't understand a thing.

In The Summer Before the Dark, which I persuaded him to read because it's short, the forty-five-year-old heroine, Kate Brown, is alone for the summer. Her husband is away and she is sure he is having an affair with a younger woman. She accepts this wryly: middle-aged women have to put up with infidelity. She takes a summer job as an interpreter for a food conference, makes friends, and has an affair. But later in the summer, when she moves into a room in a young woman's apartment, she begins to face what aging means. She lets her hair go, doesn't eat, has a bit of a breakdown, and experiments with her effect on men, walking back and forth in front of construction workers in different garb to gauge their reactions. Naturally, they ignore her when she makes herself look old. And yet she's still herself: all she needs is hair dye and expensive clothes to fit in. She is still Kate, regardless of her age. This is a realistic novel: she is not thrilled with what she learns, but she comes to terms with it. This is not a "hen lit" book where the heroine finds a new man in the end.

Well, my friend thought Kate was loony. It was one big breakdown novel, he thought, and he didn't understand that she learned from it. He doesn't understand that this is the way women live. He doesn't quite get that Kate changes. It's just an isolated breakdown to him, not related to women's aging.

My reaction to Norman Mailer is probably similar to his reaction to Lessing. Years ago, for a Women's Image in Literature course (do they still have such things?), I read Mailer's Advertisements for Myself, a collection of his essays. Good God! I do believe he said he wrote with his penis rather than a pen! And he said that women can't write.

Then I tried to read Mailer's The American Dream. I wasn't too crazy about the part where he strangles his wife. Apparently Mailer really DID stab his wife. I didn't finish the book.

So there's women's sadness and men's violence?

"You don't understand me."

I probably don't.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)